Having first come to the Nithsdale parish of Kirkmahoe in 1997, it’s a joy to still be getting to know people around here with extraordinary interests, passions and talents. Barbara Mearns is one such person. We live just a couple of miles apart but until this year we had only met a few times, although I did know about her excellent poetry collection, based on encounters with the nearby degraded peatbog, known as the Lochar Moss.

Barbara embodies some of the sentiments of the Quotidian pages. She treads gently on the earth, observes the natural world close up, and records what she sees. Her blog exudes the pleasures of writing and reading the environment. Her poetry distils these into crafted stanzas that sit lightly on the page. Her photographs provide respectful close-ups of local flora and fauna. Her observations provoke new questions, from which her learning continues. Listening to her talk about birds, animals, trees and plants is to be taken into a nearby world that is so easily missed as we bustle about daily tasks.

I was therefore very keen to learn more about her approach to these things, and delighted when she agreed to join the list of interviews with creative people in Dumfries and Galloway, for each of whom I have such admiration.

Can you say a little about where you were born, your upbringing, and schooling? What were your main early interests?

I was born in Greenock and went to Greenock Academy Primary for four years, then St Columba’s in Kilmacolm.

I can’t remember a time when I wasn’t fascinated by wildlife. I enjoyed walking to and from primary school on my own, as I could stop and look at butterflies, or gather conkers, or twirl sycamore seeds. In my earliest outdoor photos, I’m usually clutching a bunch of wilting wild flowers. I collected a lot of seashell species, mostly on wonderful summer holidays on Arran. My father was a teacher, so we took a cottage for a month every summer, and there I was allowed to explore more on my own as I got older, guddling in rock pools, or watching birds with binoculars passed down from my grandfather. At first, I tried to learn about everything, but then decided to concentrate on birds.

I was very fortunate that extra-mural birdwatching classes started at Greenock Arts Guild when I was 13. My mother signed us both up, and though she had no previous interest, she really enjoyed the field trips and the good company. Twice a month the group would go out locally, or in a coach to sites as far away as the Bass Rock, Loch Lomond or the Solway. During those four years I learnt a lot from more experienced birders, but more importantly, discovered I wasn’t as weird and unique as some other girls thought I was!

My brother was seven years older. He gave me my first camera, and (very patiently!) taught me to use it. I’ve always been grateful for that, as I’ve enjoyed taking photos ever since, and it’s been a useful skill in many situations.

I would have liked a career in wildlife and conservation, but although I was good at biology, I was poor at maths and other sciences, and there were few opportunities then, especially for girls. But the door opened later, when I got involved with A Rocha …

After school did you go on to college or university … and to study what?

I studied Occupational Therapy in Edinburgh. I only worked as an O.T. for seven years, but it was good training for life.

At what point did you move to Dumfries and Galloway?

I came to Dumfries for my first job, in the Child Psychiatry Department at the Crichton Royal Hospital. Soon afterwards, I met Richard (Rick) who was then studying Peregrine Falcons across Dumfries & Galloway and we married in 1981. After Rick and I started to write books together, about the early naturalists, I never went back to O.T.

Tell me more about how that unfolded. What were you and Rick focused on at that time, and how did your collaboration progress?

In 1983 we camped on the Alaskan tundra, photographing waders. Many of the birds we watched, such as Steller’s Eider and Wilson’s Warbler, were named after people. We wondered who they were, and on returning home, I found a biography of Wilson, the ‘Father of American Ornithology’ who grew up in Paisley, not so very far from Greenock! After emigrating to the USA, he travelled thousands of miles by walking, riding and rowing, often alone, painting and studying the birds along the way. There was a fascinating human story behind every eponym, so we researched all the people who had European birds named after them, and Academic Press published our first book, Biographies for Birdwatchers. Two more books on the early naturalists followed. Each time we divided the characters between us, doing our own research and writing, after which I was ready for a change!

Can you describe the work of A Rocha International and the part that you have played in it?

A Rocha is an international family of Christian conservation organizations. The work began with a bird observatory in the Algarve, which Rick and I first supported as volunteers, but from 1997 to 2017, from our home in Kirkton, I ran the A Rocha International Office. During that time, projects sprang up in 20 countries, wonderfully varied, but typically with a focus on practical conservation, environmental education and church engagement. I was able to visit some, in various ways, though most of the time I was in the office, busy with admin, editing and emails.

One spring I took a group of supporters to Lebanon, to see the Aammiq Wetland which A Rocha protected by working with the landowner, tenant farmers and nomadic Bedouin grazers. Another time I helped to lead a supporters’ holiday on the Kenyan coast, where A Rocha is studying and helping to protect the local coral reefs, mangroves and dry, coastal forests. I joined our Conservation Science Director on one of his visits to Ghana, which was a great opportunity to meet schoolchildren in A Rocha clubs who were practicing agro-forestry, and to join some of our ecologists as they met with villagers to restore degraded forests, wetlands and grasslands.

Sometimes Rick and I combined our holidays with an A Rocha visit. In 2005, whilst working on a biography of John Kirk Townsend (an American ornithologist who crossed the Rockies in 1834 and provided J.J. Audubon with many new birds and mammals) we followed in Townsend’s footsteps, then popped over the border to visit the A Rocha Canada team, discovering how they care for people and places.

Despite all this travelling and international engagement, Dumfries and Galloway and in particular Nithsdale, seem to occupy a special place in your life. Can you tell me about what the area means to you and the activities you have pursued locally?

I have lived in the Nith Valley for nearly fifty years (Rick for slightly longer) and I don’t think we’ll ever want to move elsewhere. By staying in one place and recording birds, dragonflies, moths and butterflies long-term, we’ve seen remarkable changes in the distribution of some species. Many are moving north because of climate warming: for example, twenty years ago, we never saw Migrant Hawkers or Emperors here, but now these two dragonflies are locally widespread.

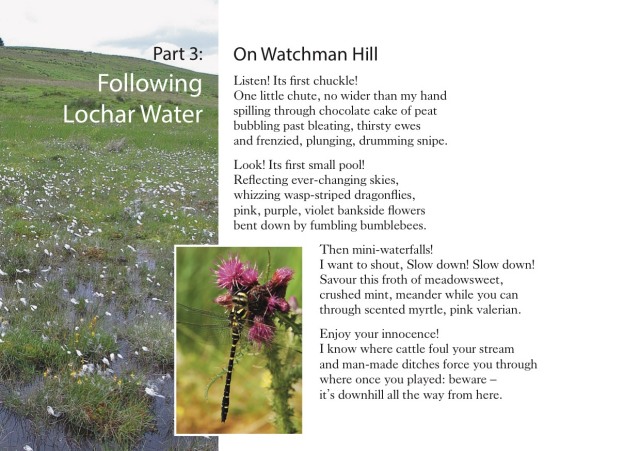

About ten years ago, I decided to focus for a while on writing poetry about the Lochar Moss, which was once one of the largest raised bogs in Europe. At first, what I noticed most was the terrible degradation wrought by nearly three centuries of draining for farming and forestry, but so much peatland wildlife still thrives there that my laments increasingly turned to delight. I followed the Lochar Water from its first hilltop trickle through freezing fog, winter floods and spring sunshine to its final meanders through coastal meadows. I also enjoyed writing imaginatively about human interactions with the local bogs over 6,000 years, inspired by the Bronze Age dug-out canoe and the brass torc from the Lochar, and accounts of local women who, during the Great War, made thousands of sphagnum moss wound dressings for use at the front.

Nowadays what would be the rhythm of your field work and writing, say across a whole year?

From late spring to autumn I do as much dragonfly recording across Dumfries and Galloway as time and weather allow. It’s easiest on sunny days, when adults are mating and egg-laying at ponds or streams, but if I have walked a long way to a new site and then it turns cold and wet (not unusual) I will get out my trusty plastic colander and dip for larvae.

Rick and I run a light trap for catching moths in our garden all year round (sporadically, when the weather is suitable) but when moths are more numerous from May-October, we also trap in poorly recorded areas across D & G. Rick takes the initiative and does the time-consuming work of identifying the more difficult species − and submitting all the data − but I enjoy helping him. We particularly like setting our traps on the Wigtownshire coast (see featured image), as we have often had surprises there, either rare migrants or unexpected resident species. From late May to early July (the flight period of montane micro-moths) we try to get into the hills if there are any calm, sunny days, as the conditions have to be just right for us to find them.

Birding we can enjoy all year round and the weather is much less critical.

In winter we try to catch up with all the friends, family and chores we’ve neglected during the fieldwork season! I also have more time then for writing.

I blog about the wildlife of the Nith: writing helps me to look more carefully and to ask questions to which I often don’t know the answers, so I keep learning.

I also enjoy taking photos and doing press releases for Dumfries Baptist Church, where Rick and I are both involved. There is often a good story to share.

And any further projects you hope to pursue?

I love islands and have been to many around the British coast, but there are still some Hebridean islands which I particularly want to visit.

Further details

All Photographs: R&B Mearns, in order of appearance:

- Emporer egg laying. Caerlaverlock WWT Reserve.

- Heron fishing at the Caul, river Nith.

- Frog in Spring.

- Two Commas on Rowan.

- Small Pearl-bordered Fritillary

- Canary-shouldered Thorn Moth.

- Sphagnum.

- Sundew with trapped insect.

- Cottongrass.

- Bog Rosemary.

Barbara can be contacted through her Wild Nith Blog and can guide you to her various publications http://www.mearnswildlife.wordpress.com

Books by B & R Mearns www.mearnsbooks.com

Poetry:

Mearns, B. Peatland Poems from the Scottish Solway 2018.

Ewing, L. & Mearns, B. Bairns & Beasts 2012.

Biography:

Mearns, B. and Mearns, R. 2022. Biographies for Birdwatchers, The Lives of Those Commemorated in Western Palearctic Bird Names, Revised and expanded edition Mearnsbooks

Mearns, B. and Mearns, R. 2007. John Kirk Townsend. Collector of Audubon’s Western Birds and Mammals, 389 pp. Mearnsbooks

Mearns, B. and Mearns, R. 1992. Audubon to Xantus. The Lives of Those Commemorated in North American Bird Names, 580 pp. Academic Press, London.

Mearns, B. and Mearns, R. 1988. Biographies for Birdwatchers. The Lives of Those Commemorated in Western Palearctic Bird Names, 490 pp. Academic Press, London.

Wildlife:

Pollitt, M., Conway, L. & Mearns, B. 2019. Dragonflies & Damselflies in South West Scotland, 44 pp SWS Environmental Information Centre.